JOHN FRAWLEY: WHAT IS PREDICTION?

What is happening when we predict? Is destiny negotiable?

What is Prediction?

John Frawley's article

No timing is given: but apart from that, this prediction is as specific as could be wished. The Weird Sisters were apparently unencumbered by the necessity for secondary progressions or even a horary chart. Like us, however. they were in the business of predicting, and their predictions are worth considering.

Once Macbeth had heard this prediction he acted in a certain way. Any of us, had the prediction been made to us, would have acted in a certain way: most of our 'certain ways' would have been to laugh it off or ignore it, doing nothing to further it, but mentally filing it away to see if it came true. If this were all we did, the prediction would not work. But the prediction has not been made to us: it was made to the man for whom it would work.

«You've just become Thane of Glamis. You 'll soon be

Thane of Cawdor. You'll then be King of Scotland.»

«Macbeth», William Shakespeare.

«Macbeth», The Weird Sisters.

Macbeth does briefly consider doing nothing, but dismisses the possibility that fate will crown him king without his own assistance. This prediction was made to Macbeth because, once made, he was the person who would act upon it, and act with sufficient power and resource to make the prediction true. Had it been made to someone else - Banquo, for example, who seems a decent enough chap and unlikely to murder the king - it would probably have been wrong. That is, had either the prediction or the person to whom it was made been different, the result would have been different.

The correct outcome of this prediction depended on it being made to a certain person at a certain time: that is, it depended on the reality of the situation. Real, and exactly as it was.

«You'll be quite safe until Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane; and none of woman born shall harm you.»

«Macbeth», William Shakespeare.

This too is specific prediction, and it too is based in the reality of the situation. The one who is not of woman born is not some hideous monster roaming the highlands in search of prey: it is a man Macbeth has grievously wronged, who happens to have been from his mother's womb untimely ripped. Similarly.

Birnam Wood does not come to Dunsinane as a random freak of nature, but as the tactic of a superior army attacking Macbeth's stronghold as a direct consequence of Macbeth's actions.

The idea that prediction is rooted in reality, and can give flower only to whatever seed happens to have been sown in that particular soil is crucial to an understanding of what prediction is - and of what it is not. Horary charts show this clearly: they give an accurate analysis of the present situation, from which the astrologer can draw conclusions about the future, in a manner more akin to Sherlock Holmes than Mystic Meg.

Horary astrologers are often confronted with the question "What if?":

REAL LIFE, AS IT IS

— What will happen if I leave my husband?

— You're not going to leave your husband.

— But what will happen if I do?

This question is unanswerable. We cannot deal with the hypothetical, for if anything is changed from the reality that we have, anything can happen. Our chart is cast for a moment in reality: we cannot cast a chart for a moment that does not exist.

"If I were in the Olympics, would I win?" As things are now, no - I can't run fast. But if reality were changed, if I could fast enough to qualify for the Olympics, I might win. We cannot alter just one tiny part of reality: we alter all or nothing.

LILLY AND HIS FISH

The great seventeenth-century astrologer, William Lilly, had ordered some fish and a bag of Portuguese onions to be sent from London to his home, just up-river in Hersham. Instead of delivering the goods, the warehouseman came to Lilly and told him the warehouse had been robbed and the fish stolen. Lilly set a horary chart to find the thief.

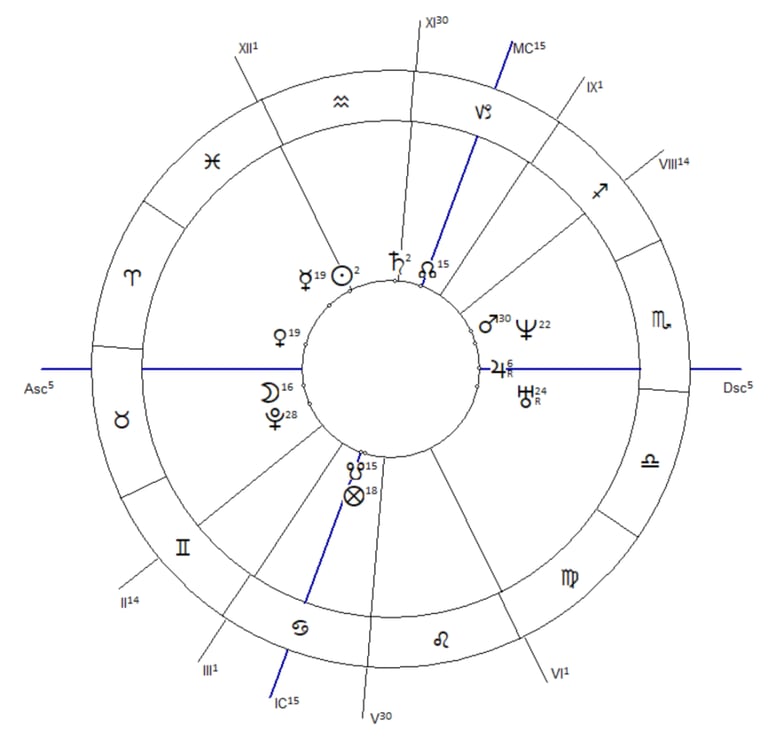

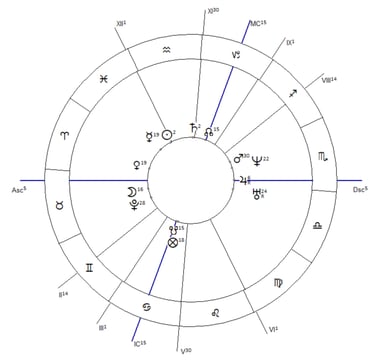

WHERE ARE MY FISH?

FEB. 20th,1638. 9-00 a.m. LMT. Hersham (51N 24, 0W 27).

In a question of theft, a peregrine planet in an angular house often shows the thief, while the Sun or Moon in the Ascendant in one of its own dignities shows the thief will be found out. Here, Jupiter is peregrine and on the cusp of the seventh, while the Moon, in its exaltation, is in the Ascendant.

Jupiter is the natural ruler of the rich and noble, and Lilly decided that a gentleman wouldn't stoop to stealing a fish, but he did take note of the sign that Jupiter is in: Scorpio, a water sign. The Part of Fortune, which signifies the querent's 'treasure' is in Cancer, another water sign, while Mercury, which rules the second, the house of the querent's possessions, is in the third water sign, Pisces. Considering this evidence and the circumstances, he decided that the thief must work on water and the fish must be in some moist place (Part of Fortune in Cancer) or a low room, as the Moon - dispositor of Fortuna - is in the earth sign Taurus.

The Moon applying to the Lord of the second house in a theft chart shows that the stolen goods will be found. How much they can be recovered depends on the condition of the two planets. Here, the Moon applies to a sextile of Mercury, ruler of the second, showing that Lilly would hear of the fish. The Moon in Taurus is strong, but Mercury is in both its fall and its detriment in Pisces, making it very weak.

Mercury is, however, in its own terms and forms a trine with the Part of Fortune: this assuages the weakness a little. Balancing the testimonies, Lilly judged that he wouldn't recover the fish intact, but that he would get some of it back. If both the planets had been weak, the fish would have been found, but he wouldn't have been able to recover any of it. So the chart has told him he will discover the thief and recover some of the goods.

Apart from a peregrine planet in an angle, the thief is also shown by the seventh house. Its ruler, and also dispositor of Jupiter, is Mars, which is on the point of leaving its own sign, Scorpio. This suggested that the thief had recently moved house. After making enquiries, Lilly heard of a fisherman with a reputation for thieving who had just moved ro a house by the river, as was shown by the emphasis on water signs. His appearance was typical of Mars combined with Jupiter: he was tall and well-built with fair complexion and reddish-yellow hair.

Hans Olaf Halvor Heyerdahl. The old fisherman.

Armed with this combination of astrology and detective-work, Lilly approached the local magistrate, who granted him a warrant to search the man's house. He found part of the fish, at which the thief confessed all, saying that the rest of the fish had already been eaten. Lilly grumbled at the man's wife about the fate of his onions - not knowing what they were, she had made soup out of them - but then relented and let them keep the remains of their loot.

The discovery of the thief and the retrieval of the fish are predicted, quite clearly and according to set rules, in the chart; but these predictions depended on certain actions to make them happen. These actions need not, apparently, have been taken.

The chart guided Lilly to the thief. Having found the thief, many people would not have confronted him. This was a small community: Lilly might have been frightened of the consequences of his accusation, or uncertain of his judgement and scared of embarrassment if he had got it wrong. He wasn't. This was the same Lilly who walked from Leicestershire to London to find work. who performed a mastectomy on his master's wife, who risked execution by plying his trade at high level during the Civil War: he wasn't one to back down from a challenge.

William Lilly

To allow the prediction to come true, Lilly had to be in a position to obtain a warrant to search the thief's house. Few modern astrologers would find much sympathy arriving at their local police station waving a chart and claiming to know who had stolen their belongings. Lilly had a strong reputation as a worthy citizen and an accurate astrologer. He was the magistrate's social equal, and he would have found no problem in obtaining the warrant.

Lilly's character and circumstances are an integral part of the chart. Had they been different - had he, for example, been timid, or known for getting his predictions wrong - the chart would have been different. It is reasonable to assume that had the circumstances, including Lilly's character, been different, he would not have asked this particular question at this particular time. If, for example, he were timid, he might have been busy being bullied at that moment; if he were not the magistrate's social equal, he might have been busy digging ditches; if he had a poor reputation as an astrologer, he could probably not have afforded to order the fish in the first place.

The prediction is as much an integral part of real life as any other action: it is not something appearing completely out of the blue, unconnected with either what has happened already or what is going to happen in the future. It follows what has already happened by a natural progression, and if what has already happened - that is the current situation - were different, the prediction would be different.

There is only one possible set of circumstances that could lead to that exact prediction being made at that exact moment. That set of circumstances is the one, and the only one, that has actually arisen. Anything else exists only in the world of hypothesis, and as such is beyond our consideration, for in a hypothetical world, anything can happen at any moment. With an omnipotent deity, this is, of course, possible anyway, but it does tend not to happen.

THE DESIRE FOR MAGIC

For our purposes, making real predictions in a real world, the hypothetical does not exist. The idea that it does, or should, betrays our true interest in prediction. We do not want to know what is going to happen in the future: we want the possibility of shaping what will happen to suit our own desires. We do not want to know the truth: we want one particular answer and we want that answer to shape reality for us, just as I do if I pluck leaves from a stem and find 'she loves me'. I want this to make it true.

This is not what prediction does, and despite our wishes we are well aware of this. The days when the astrologer either could, or would at least attempt to, twist fate on our behalf are long gone. Prediction does not give us a clean slate from which we can form the future that we want; it does not release us from our past any more than it makes us five pounds thinner. It is not an entry into the world of "What if", where all desires are magically fulfilled.

J.W. Waterhouse. The Magic Circle.

This is probably no bad thing, for our consciousness of our own true will is so patchy that if prediction were able to arrange fate for us, we would be like the people in the fairy tales, forever using their last wish to sort out the disasters they have caused with the first two. The closest we get to a true vision of our own wills is usually the cold, clear overview we are granted by an astrological chart. That with which we usually deal is less will than whim.

That the hypothetical is not granted us is a blessing; that we are aware of it is a curse. Comparisons are indeed odious, and "what if" blights our lives:

— What if I were with her instead of my wife?

— What if I had a Ferrari?

— What if I'd ordered the steak instead of the fish?

That the hypothetical does not exist is the lesson of prediction: a lesson far more valuable than any individual prediction we may make. There is no comparison, because there is no alternative reality with which to compare things. There is no such thing as 'what if'.

We are indeed looking into the seeds of time and saying which grain will grow and which will not. And, just as seeds of flower and plant, these seeds too grow only unto their nature. Were it not thus, prediction would be impossible. That it is thus, resolves the apparent conflict between prediction and free-will. For our will is rooted in what we are, and can work only according to our nature.

Prediction is not magic, summoning up the thing desired with none of its consequences. Macbeth forgets this: he has no right to his thing desired, and so can obtain it only by murder, suffering as a result. What prediction is, is a means of selection, by which we can gaze at the infinite array of possibilities and discover which is real. Looking, for example, at a horary chart, the aspect that connects the two significators and enables us to judge "Yes, this will happen" is like a bridge thrown across a vast gulf of shadows, the only pathway into the future.

Prediction traces the infinitely narrow pathway of our will, winding like a thread from birth to death, and determines whether or not any particular event falls on that path or not. What does, is real; what does not, is not. It is the mental equivalent of reaching out an arm in a pitch dark room to find what is there. No more; no less.

THE ARTICLE IS AVAILABLE IN RUSSIAN TRANSLATION HERE.

NOTE: All articles by John Frawley on our website are published and translated with his personal permission. The original article can be found on John Frawley's website, under the «Magazine» section: «Issue 1, «What is prediction?».

Subscribe to our blog