IN DEFENCE OF ASTROLOGY

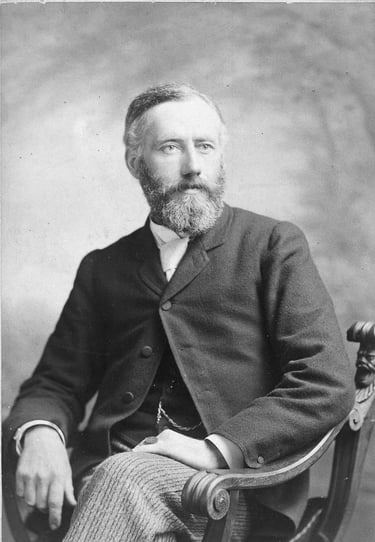

Theosophist W.Q. Judge in defense of Astrology.

In Defence of Astrology

Could we ever have imagined that a composition bearing such a title would emerge from our pen? This seems particularly improbable when one considers the irreparable harm inflicted upon the art of astrology in the early twentieth century by the theosophist Alan Leo, who, in essence, gave birth to modern astrology with his oft-quoted assertions: “character is destiny” and “astrology does not predict”. These declarations, uttered during a judicial proceeding, marked his virtual renunciation of the true predictive craft — an art he never fully mastered — in favour of the Frankenstein’s monster he subsequently created. Yet, without the contributions of the venerable Jung, or the humanist Dane Rudhyar, this creation might not have achieved such widespread acclaim among the masses. To this day, this amalgam of psychology and karma, cultivated upon the barren soil of materialistic astronomy, is mistaken by the majority for genuine astrology. We have remarked upon this misconception in our writings on numerous occasions, often with considerable disdain, and thus there is little need to dwell upon it further. Nevertheless, it came as a surprise to us that, among the theosophists of yore who explored astrology, one might discover a truly discerning mind. It is through such an individual that not only theosophy but also astrology, within theosophical circles, might find justification.

It might be supposed that among the followers of theosophy, there were many who wrote about or took an interest in astrology. One need only consider the likes of Manly Palmer Hall. Yet, Hall’s connection to astrology was as remote and purely theoretical as that of Claudius Ptolemy himself. Though Hall possessed greater erudition, the aridity of his intellect becomes immediately apparent upon perusing some of his works. He understood astrology no better than did Alan Leo. While the former’s writings may find some vindication in the historical aspects of astrology, which he elucidates with considerable skill, the latter’s efforts invite nothing but the sternest and most admonitory criticism. This suggests that the mastery of astrology eludes even those endowed with great intellect, as in Hall’s case, or practical acumen, as in Leo’s. It demands not only a particular cast of mind but also talent, vocation, and years of patient study, replete with errors and successes, to tread the path toward mastery.

In truth, we have never harboured any aversion to theosophy as a philosophy. We share the majority of its perspectives, save for the views of the aforementioned theosophists regarding astrology. Indeed, we too hold that truth stands above any religion. The motto of the Maharaja of Benares — “There Is No Religion Higher Than Truth” — adopted by the Theosophical Society as its guiding principle, serves also as our own lodestar in life.

As presented to the broader public, the theosophical perspective on astrology lacks truth, offering instead mere distortion. Yet this does not imply that no theosophist ever grasped the true nature of astrology.

Perhaps, had modern theosophy more closely aligned itself with the life of William Quan Judge — one of the co-founders of the Theosophical Society — as an example of the true theosophist, the movement might have enjoyed a brighter future. Regrettably, for some peculiar reason, Judge stands somewhat apart in theosophical circles, particularly within the Russian-speaking world. His works have not gained widespread recognition. Attention invariably turns to the writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, or Alfred Percy Sinnett. Yet, a study of Judge’s works might cast more light upon theosophy than all that has been said or done since Blavatsky’s passing. His letters to friends and colleagues bear a resemblance to the moral epistles of Seneca to Lucilius or the meditations of Marcus Aurelius, so rich are they in ethical purity and wisdom. They exemplify a humble and virtuous life devoted to service, rendered in a theosophical spirit. It is his article, published in The Theosophist in 1882, that we wish to present hereafter as a vindication of astrology among theosophists. Entitled “Astrology Verified”, it is noteworthy not only for its sound and practical approach to the predictive art but also for its considerable insight into horary astrology, with which Judge was acquainted through personal, including practical, experience.

In the pages of The Theosophist, Charles K. Massey remarks that we are presently but imperfectly acquainted with the science of astrology, and that, as it is currently presented, it is not always reliable. His observations regarding its unreliability justly apply to that branch concerned solely with natal charts, a view with which I concur, having encountered numerous instances wherein predictions based upon such charts proved erroneous. This division of the science is exceedingly complex and fraught with difficulties that demand years of diligent mastery. Can we, then, be astonished by the errors committed by a professional astrologer? He cannot afford to devote years to patient labour, for, standing but one foot upon the threshold of this venerable art, he begins to dispense his calculations and prognostications.

The first three branches of this science — natal astrology, which foretells the destiny of individuals; mundane astrology, which predicts the fate of nations, the outbreak of wars, and epidemics; and astrometeorology, which prognosticates weather based upon certain planetary aspects — cannot be readily comprehended or employed, for they require not only great perseverance over several years but also a sound education. Yet there exists another division, known as horary astrology, which addresses questions posed to the astrologer at any time concerning any matter of interest to the inquirer. Upon careful study, this branch may be quickly mastered, and its application rewards the investigator with precise answers, insofar as we may hope for such in this illusory world. One need not await many years before, with confidence, answering questions or resolving issues, save for matters of predestination or the determination of auspicious days and hours for undertaking an endeavour.

Zadkiel, a learned man and former officer of the British Navy, asserts in his writings on this subject that any individual of average intelligence may swiftly learn to navigate horary astrology: discerning with whom to associate, what to avoid, and the outcome of any current or proposed undertaking. That Zadkiel was correct, I have had ample opportunity to verify over several years. We also have Lilly, who preceded Zadkiel and echoed his sentiments. In his book An Introduction to Astrology, Lilly recounts hundreds of instances wherein horary astrology yielded accurate responses to posed questions. It was Lilly who foretold the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the plague that claimed so many of its inhabitants. Regardless of how much the so-called scientific world may scoff, this remains a well-substantiated fact.

From my experience with horary astrology, I have learned that certain individuals lack the innate disposition requisite for correctly answering a question that another reader of the horoscope might resolve accurately; conversely, one who consistently provides correct responses to horary queries may falter with a natal chart.

It is permissible to name deceased professors, as this precludes any accusation of promoting them. In New York, there resided until recently one Professor Charles Winterburn, who practised medicine and occasionally horary astrology. I consulted him on many occasions, and he accepted no fee; I cannot recall a single instance in which he erred. His mind was capable of furnishing a reasoned response to any astrological query. With profound regret, I learned of his demise. From the many questions he addressed, I have selected a few, along with some others answered by different astrologers, myself, and other amateurs.

Two years ago, precisely at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, I signed a contract pertaining to the use of electricity. The terms appeared favourable, and all parties anticipated substantial profit, yet all were curious as to the cost. I submitted the question to Dr. Winterburn and three other astrologers—none aware that the query had been posed to others, and one residing at a distance—“At 3 o’clock this afternoon, I signed a contract; what will come of it?” No further details were provided. With remarkable unanimity, all responded that no good would ensue and that I should withdraw. Dr. Winterburn suggested I might derive a small sum from the contract, but that expenses would consume it; another astrologer noted that the contracting parties were at odds and lacked resources. This proved true. Astrology allotted eleven weeks for the matter’s resolution. In eleven weeks, the affair concluded, and I gained nothing therefrom.

Subsequently, I engaged in a venture somewhat connected with the government and the production of a certain commodity. To gather evidence for or against astrology, I obtained predictions, set them aside unread, and paid them little heed. The enterprise promised fair prospects, but eventually, I observed an unfavourable turn and examined the responses. As before, they unanimously advised against proceeding. All foresaw some financial gain, yet also significant expenditure. Dr. Winterburn, in reply to my letter on this matter, stated: “On the twentieth of this month, you will receive some compensation, but thereafter you should abandon the venture. Yet I perceive that you will leave it, and it shall vanish entirely from your sight.” On the twentieth, I received payment for the last time, and from that day to this, I have had no further involvement, as though I had never heard of it.

In 1879, I contemplated relocating my office and sought Dr. Winterburn’s astrological forecast. He replied: “Do not move yet; the proposed location is unfavourable, and you would encounter great trouble and expense; wait.” Soon, another premises was offered in a different building, appearing no better. Dr. Winterburn and other astrologers, with the same unanimity, advised: “Relocate; the new offer is sound and will please you in any case.” As the new space was both good and inexpensive, I moved — not because astrology so predicted, but for its merits. Strangely, eight months later, the place they had warned me against — which they knew nothing of in terms of location or condition — was occupied by masons and carpenters; a wall was demolished mid-winter by municipal order, and the site was exposed to cold and filth for half a year. Had I been there, the cost would have been considerable, and the inconvenience immense. Let it be noted that, when their responses were received, neither the landlord nor the government intended any alteration.

When an attempt was made upon President Garfield’s life, my friends and I cast a horoscope for the event, which, by all rules, portended his death. I predicted his demise within a week. We erred in the timing, but not in the astrological principles.

Before my father’s death, Dr. Winterburn, who had never met nor seen him, declared: “The signs are unfavourable; I believe the calculation of time and place is fatal. He will die within a few days, but his passing will be gentle and peaceful.” He passed fifteen days later, quietly and easily, as a child falls asleep. The astrologer had been asked but one question: “My father is ill; what will become of it?”

Such are some of the numerous instances attesting to the accuracy and veracity of this ancient art. I could cite hundreds more.

These experiences have led me to conclude that horary astrology is a reliable method of prediction. The ancients, whose minds were untrammelled by the fetters of fanaticism or theology and who possessed an ardent desire to benefit the “great orphan—humanity”, dwelt chiefly in India and Egypt, where they studied nature. They discovered that nature constitutes one vast mechanism, its wheels revolving within one another. By calculating the motion of a single wheel and understanding its rhythm, they obtained a key to all. Thus, they took the planets with their celestial orbits, along which they move, and devised a system, grounded in experience and universal law, enabling them — and enabling us — to guide the uncertain steps of man through the dark and arduous valley of this life. Anxiety ranks among man’s greatest and most insidious foes, shackling his energy and thwarting his goals. If astrology can alleviate anyone’s distress during a crisis, ought we not to promote its study and dissemination? It has often spared me the anxiety I would otherwise have endured for months. It can do the same for any individual.

May the light shine forth from the East, where astrology was born. May those whose ancestors furnished Claudius Ptolemy with the materials for his Tetrabiblos aid us in deepening our understanding and advancing this most ancient art.

W.Q. Judge: Astrology Verified

New York, 28 January 1882

William Q. Judge, Member of the Theosophical Society

Subscribe to our blog